On Monday of this week, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced plans to launch a new military incursion into Syria. Turkish movement around the border with Syria has been overshadowed by news coverage of Turkey’s intent to veto Sweden and Finland’s application to join NATO. As NATO can only accept new members through unanimous consent, the Turkish position has made things complicated. However, Turkey’s position on Sweden and Finland acceding to NATO and plans to launch a military operation against Kurdish groups in Syria are intimately connected.

Publicly, the Turkish state has made it clear that it will refuse to accept Finland and Sweden into NATO over the Nordic states’ position on the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG). Turkey accuses the YPG of being a Syrian branch of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), a left-wing political party that has waged a guerilla war against the Turkish state since 1984 in a struggle to achieve Kurdish autonomy in the southeastern Kurdish majority region of Turkey bordering Syria. It is important to note that despite these allegations, the YPG has continued to maintain independence from the PKK and that its operations are confined to Syrian Kurdistan fighting against Islamist jihadist groups.

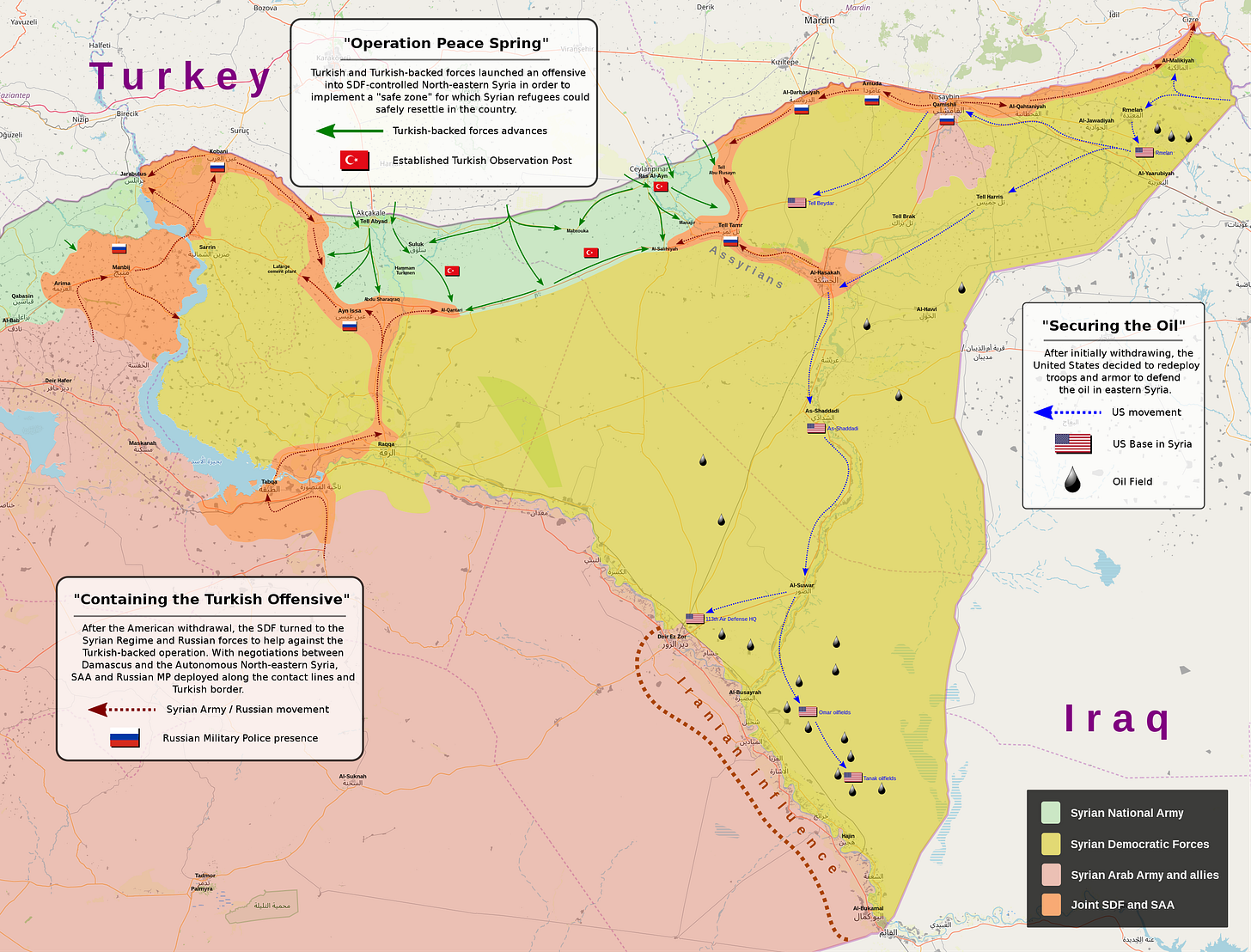

Nevertheless, Turkey views Kurdish autonomy as an existential threat to the Turkish state. In addition to the aforementioned guerilla war with the PKK, Turkey has conducted several military operations against Kurdish groups in northern Syria. In 2019, Turkey launched a major offensive into Syria in what was dubbed Operation Peace Spring. According to Turkish officials, the operation aimed to create a 30 km deep buffer zone from the Turkish-Syrian border and expel the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a YPG-affiliated group, from northern Syria. Despite the SDF’s key role in the US coalition that defeated the Islamic State, Turkey designated it a terrorist organization and moved to defeat it. As part of the operation, the Turkish military and their Islamist proxies, the Syrian National Army (SNA) conducted what can credibly be described as a campaign of ethnic cleansing, expelling Kurdish communities from their historic homes to clear the land for the forcible resettlement of Syrian refugees that Turkey claimed were voluntary returns.

Turkey has a long history of meddling in Syria. Since independence in 1921, the Turkish state claimed the Syrian province Alexandretta as part of Turkey, despite the population being majority Arabs. At the time, Alexandretta was absorbed into the French mandate of Syria, but in 1938, the French ceded Alexandretta to Turkey as part of a diplomatic effort to prevent a Nazi Germany-Turkey alliance. Alexandretta was renamed Hatay province, street signs were replaced with Turkish counterparts, and the province remains part of Turkey.

Still, as a result of Turkey’s offensive in 2019, western countries including Sweden and Finland issued an arms embargo and condemned Turkish aggression against the YPG. Sweden in particular was a popular destination for Turkish dissidents fleeing persecution abroad. The country is home to a significant Kurdish diaspora and refuses to extradite those deemed criminal by the Turkish security apparatus. It was this response – both rhetorical and political – that remains a point of contention between Turkey and NATO.

Turkey’s refusal to allow Sweden and Finland into NATO rests on these sore spots. For one, the Turks demand the repatriation of some 30 individuals living in Sweden that they deem PKK affiliated terrorists. Turkey has also requested the processing of a sale of US F-16 airplanes to the Turkish Air Force, a sale that has been suspended following Turkey’s purchase of Russian S-300 air defense systems. In other words, Turkey is using its veto within NATO as a bargaining chip to extract as many concessions from Sweden, Finland, and the US/NATO as it can.

Following Monday’s announcement by Erdogan, Turkey’s National Security Council said on Thursday May 26th that while existing and future military operations in its southern border did not target the sovereignty of other countries, they are deemed necessary for the country’s security.

So, what does this all mean? Well, with the world distracted by the war in Ukraine, Turkey believes this is the ideal time to move on the YPG in Syrian Kurdistan. Turkey has also recently conducted military operations on Kurds in Iraq. Russia’s incursion into Ukraine has also given Turkey an unexpected advantage. The 2019 Turkish offensive ended with a ceasefire organized by both the US and Russia, the latter playing a considerable role in Syria as the backers of Bashar al-Assad’s government in Damascus. I suspect that not only is Russia distracted by the fighting in Ukraine, but it may perhaps want to limit Turkey’s support of Ukraine, which until now has included sales of the formidable Bayraktar TB2 armed drone to the Ukrainian armed forces. As such, Turkey can use that leverage to get Russia to disregard the ceasefire and give the Turkish army a freer hand in moving against Kurdish groups in Syria and Iraq.

The 2019 operation carved out two pockets of Turkish and SNA control in northern Syria. The first pocket lies on the western banks of the Euphrates River, around the town of Jarablus. The second zone of Turkish control lies further east, a strip of land south of the border extending from the towns of Tell Abyad and Ras Al-Ayn. The two zones are separated by the Kurdish controlled areas of Manbij and Kobane. Following the 2019 ceasefire, Russian forces and the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) of Assad’s government were deployed to both Kobani and Manbij to act as a buffer between the Turks and the Kurds. Despite some minor clashes, the post-2019 ceasefire stood until now.

Now, with Russia’s (and the world at large) attention elsewhere in Ukraine, Turkey may consider it the right time to seize Manbij and Kobani, thereby connecting its currently separate zones into one large band of territory stretching south from the Turkish-Syrian border deep into Syria. Turkey can then relocate Syrian refugees to this area alongside its Islamist clients, the SNA. It is hard to ascertain the size of the Russian forces stationed in those cities as of now, but Turkish intransigence towards NATO suggests that the Turkish government may find common ground with Russia and strike a deal that involves pulling the latter’s forces in northern Syria out and clearing the way for Turkish attack.

For Erdogan, there is an even an added bonus of the rallying effect of a military offensive against Kurdish groups on Turkish nationalism. The Turkish economy has been devastated by Erdogan’s insistence on keeping interest rates low, and the Turkish lira has plummeted in value. An escalation against what the Turkish state media refer to as Kurdish separatist terrorists would be a welcome distraction from headlines on the economy.

Personally, I am hesitant to accept this argument. While I am sure a war would be a boon for Erdogan among Turkish nationalists, I don’t think talks of incursion into Syria are necessarily a self-serving plot for Erdogan’s ambitions. There are many in the Turkish state and military who have been baying for just a move for years. Turkish nationalism is not to be scoffed at. It may be difficult for Western liberals to understand, but if there is one place where the concept of a nation-state as a polity belonging to a single nation with a single language, ethnicity, and culture was taken to its logical conclusion, it would be Turkey. Kurdish autonomy thus presents a constant threat to Turkey’s ideas of the nation, and any experiment in Kurdish autonomy just across the border in Syria would be an intolerable notion for the Turkish state. Therefore, as long as an autonomous Rojava exists, the danger of a Turkish offensive will also remain ever-present.